Paddling the Edge of the Arctic: A Kayak Expedition Through East Greenland

- Ruth Bergman

- Mar 28, 2025

- 12 min read

Beyond the Map: Drawn to East Greenland

Expedition kayaking had become more than a passion—it was a way of experiencing the world. The Arctic felt like the next frontier—wild, remote, and calling to be explored by paddle.

While searching for the perfect adventure, I came across Borea Adventures’ Wilderness Paddling in East Greenland, a ten-day kayak expedition into one of the most untouched corners of the world. Having had an incredible experience with Borea Adventures in Iceland, signing up for this trip in July 2022 was an easy decision.

With great anticipation, we prepared for our first Arctic journey—a land of towering glaciers and drifting icebergs, where seals lounge on floating ice and polar bears roam the vast, frozen wilderness.

Kulusuk or Bust: When Arctic Travel Doesn’t Go as Planned

We were set to arrive in the Arctic at Kulusuk, a small town in East Greenland. Located just below the Arctic Circle at 65°34′31″N, Kulusuk is home to about 250 people. The town’s airport, once a U.S. military base during World War II, is now served by Icelandair.

When I booked our flight from Reykjavik to Kulusuk, I was struck by the cost—nearly $1,000 for a two-hour journey. Was this typical? I asked Borea Adventures, unfamiliar at the time with the uncertainties of Arctic travel. I would soon understand.

We arrived at Reykjavik Airport (RKV) with plenty of time to spare, meeting our fellow travelers and a Borea Adventures guide. Everything seemed routine. As we took off, it felt like just another commercial flight. An hour and a half in, we spotted ice on the water below—finally, it felt like the Arctic. Soon after, the captain announced our approach. Through the windows, we glimpsed the bays and rocky mountains surrounding Kulusuk, stark and beautiful. But then we noticed the fog. The water appeared and disappeared beneath us as we descended. Suddenly, a jolt—the engines roared, and we were climbing again.

At first, we feared a mechanical issue. But no—the visibility was simply too poor to land.

We circled for half an hour before attempting another approach. The fog hadn’t lifted. Once again, we climbed sharply, denied landing a second time. Then came the news: we didn’t have enough fuel for another attempt. Back to Reykjavik.

The return flight was filled with quiet frustration. There was nothing to do but wait, so we settled in with our airline sandwiches and tried to be patient. By the time we touched down, Icelandair had already rebooked us for the next day, arranged a hotel, and provided meal and taxi vouchers. The efficiency was impressive—one of the many reasons I love Iceland and its people. With unexpected time to kill, we checked into our hotel and spent the afternoon at a cozy Reykjavik pub.

The next morning, it was déjà vu. Same airport. Same passengers. Same flight. The weather looked just as cloudy, but we remained hopeful. Once again, we approached Kulusuk. Once again, we pulled up. The tension onboard grew. We knew we could afford to lose one day without major disruptions to our plans—but missing two? That would be a problem.

On our final attempt, the fog was just as thick. I could see no more than before. Then—contact. We had touched down. The entire plane erupted in applause, celebrating our captain’s remarkable skill in navigating the nearly impossible landing conditions.

It had taken 26 hours and four landing attempts to get from Reykjavik to Kulusuk. Now, I understood exactly why the flight cost what it did.

Kulusuk: Breast of a Black Guillemot

I’ve been to small airports before—some that feel more like bus stops than commercial hubs. But Kulusuk Airport was on another level. The runway was unpaved. I hadn’t known a plane could land on gravel. Our luggage arrived on a cart pulled by a tractor. Instead of hailing a cab, we simply walked the one kilometer into town.

At the airport, we were met by Sigrún, our Icelandic guide from Borea Adventures. She was just as relieved to see us as we were to see her. To celebrate our arrival in the Arctic, she treated us to a lovely lunch at the Kulusuk Hostel, where we popped open a bottle of champagne—a toast to finally making it.

Kulusuk is a tiny town of just 250 people. Its name means "Breast of a Black Guillemot" in East Greenlandic. Our time there was brief—everyone was eager to start the expedition. We retrieved our kayaks from storage, gathered our gear, packed up, and paddled off into the dense icefield surrounding Kulusuk Island.

Seven Days on the Water: The Route, the Camps, and the Wilderness

Our expedition route took us through a network of fjords and sounds, with the largest being Sermilik Fjord—a vast, glacier-fed waterway teeming with ice. Over six days of paddling and one day of hiking, we traveled through some of the most remote and stunning landscapes on the planet.

This was a fully self-supported expedition—everything we needed, from food to camping gear, was packed into our kayaks. Aside from brief stays in Kulusuk and Tasiilaq, we camped in complete wilderness. The route was carefully planned, with each campsite strategically chosen for shelter and solitude. Every night, we pitched our tents in a cove within a cove, tucked away from the Arctic winds, surrounded by raw, untouched beauty.

For most of the journey, we saw almost no one—just the occasional distant boat along the fjord. We shared a campsite with another group only once. Each campsite had its own distinct character—towering granite cliffs, a quiet lagoon, a rolling stream, or a fjord where icebergs and whales drifted past in eerie silence.

From Theory to Practice: Confronting Arctic Conditions

The biggest variable in any Arctic expedition is the weather—a journey under sunny skies feels vastly different from one spent battling rain and wind. As with every major trip, our preparation resembled a shopping spree, mostly at REI. For Greenland, we geared up with Kokatat drysuits and fleece layers—trusted companions that had kept us warm and dry on several expeditions since, both on the water and, at times, even on shore.

We anticipated challenges from freezing temperatures, frigid water, and relentless rain. In reality, we were incredibly lucky. Daytime highs reached 7°C (45°F), with nighttime lows dipping to 3°C (37°F). Not a single drop of rain fell, and on several days, the sky was a brilliant blue, making the icebergs glow against the dark Arctic waters.

While we were eager to immerse ourselves in the Arctic wilderness, we hadn’t fully grasped what it meant to share this landscape with polar bears—the most formidable land predators. The reality set in when we learned that we’d need to maintain overnight polar bear watch. Each night, we divided the hours into shifts, with each of us taking a turn to stay awake and scan the surroundings. The instructions were simple: if you spot a bear, make noise. We kept pots at the ready to bang together, though in practice, the real response would be our guide firing a rifle shot to scare it away.

Of course, the best-case scenario was never seeing a bear at camp. Thankfully, we didn’t.

Miles in the Arctic: A Day in the Life of an Arctic Expedition

Several of our paddling days were the longest we had ever done, covering up to 28 kilometers in a single day. These were not rushed days, but the schedule was strict and deliberate.

Despite the middle-of-the-night polar bear watch, I usually woke up around 7 a.m. Maybe it was the sun—already in the sky for hours—or the quiet rustling of camp coming to life. Somehow, Sigrun always had coffee ready when I emerged from my tent. I’d take a few moments to soak in the Arctic stillness before starting some light packing.

Breakfast was at 8 a.m., usually oatmeal—warm, filling, and easy to pack. After eating, we’d break down camp and load the kayaks. Over the course of the trip, we got faster at it—helped, in part, by our gradually shrinking food supply.

On long days, we aimed to be on the water by 10 a.m. If we were late, Sigrun would offer a good-natured correction: “10:15—not too bad.”

We paddled for about an hour and a half to two hours, depending on landing spots and scenery. Then came first lunch—a quick 30-minute break where I’d eat a sandwich I had prepped at camp. I enjoyed coming up with different sandwich variations for Oren and me—and even rediscovered an old childhood favorite: butter and honey.

After lunch, we were back in the kayaks for another two-hour stretch before stopping for second lunch. Another sandwich, another short break. If I was still hungry, I’d dip into my ration of two standard-issue candy bars.

With a long way still to go, we’d get back on the water for another two-hour push. Somewhere in this stretch, I’d usually eat my second candy bar. I couldn’t look at a Snickers for a long time after this trip.

We typically arrived at camp around 6:30 p.m., and the evening routine began. Unpacking the kayaks, choosing a tent site, setting up camp, and peeling out of drysuits into warm clothes all took time. By then, Sigrun had coffee and snacks ready, and sometimes we’d even break out a bottle of whiskey for a well-earned happy hour.

On these long days, there was little time to explore our breathtaking campsites before dinner at 8 p.m. After hours of paddling, I needed calories, and everything tasted incredible. With the Arctic summer light still lingering, I’d take a cup of tea to a quiet vantage point—but not for too long. Another polar bear watch awaited, and tomorrow, another long paddle.

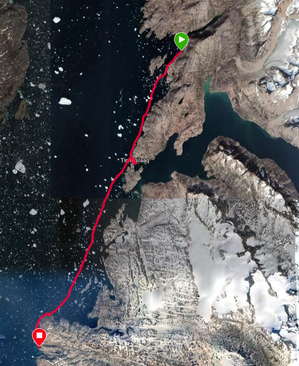

Tinitilaq: The place that runs dry at low tide

The town of Tinitilaq sits on a narrow channel that connects a sound with Sermilik Fjord. At low tide, the water level can drop so much that even a kayak may not pass—hence the town’s name, which means “The place that runs dry at low tide.”

With a population of just 150, Tinitilaq has a single store that sells everything—from food and hardware to hunting gear and entertainment. When we visited, a shipment of trampolines had recently arrived, and almost every house in town had one in the yard.

Though we saw few people, the town felt lived in. Clothes fluttered on lines strung between houses, and fresh kills lay in the harbor—a stark reminder of the subsistence lifestyle. The streets, however, were littered with broken glass, beer bottles, and other debris.

It was a place of stunning natural beauty, yet it didn’t feel cheerful.

Sermilik Fjord: Place With Glaciers

We approached Tinitilaq from the sound and landed at the harbor. Our guide led us on a hike up the hill. Perhaps I hadn’t done enough research before the trip, because I had no idea what to expect. But when I reached the top, I finally understood the meaning of the word breathtaking.

The view of Sermilik Fjord stretched before me—a vast expanse of icebergs, scattered like sculptures across the water. The sheer beauty of it triggered an overwhelming emotional response. I quite literally lost my breath and felt tears welling in my eyes.

By the time we reached Tinitilaq, I was exhausted. We had already paddled nearly 20 kilometers that day. But the moment we passed through the narrow channel into Sermilik Fjord, fatigue vanished.

Paddling across the glasslike surface, weaving between massive ice formations, and watching one towering iceberg after another drift by—it felt like entering a dreamscape. A sense of pure joy settled over me, a serene, almost meditative state where nothing else existed but the present moment.

When we reached our campsite, despite having paddled 28 kilometers, I felt a pang of disappointment that the day was over. Luckily, we would spend three more days in this Arctic paradise.

By the end of the expedition, I had memorized every color and texture ice could take. I had imagined hundreds of shapes in the floating sculptures, watched and heard icebergs calving, twisting, and rolling. And for the first time in a long while, I was at peace.

Tasilaq: Looks Like a Lake

We crossed the island on foot to reach Tasilaq—a demanding hike that tested both endurance and balance. The route took us up a steep, loose-gravel mountainside, across an icefield, and through several rushing streams. On the ascent, we had a final sweeping view of Sermilik Fjord, evoking the memory of weaving between towering icebergs. On the descent, we followed a winding stream through alpine landscapes, leading us toward the fjord below.

After 22 kilometers of hiking, we were more than ready for the comforts of The Red House, our guesthouse in Tasilaq. Of all its amenities, the most exciting was the shoe dryers in the entry hall. Even after a wet day, it felt like pure luxury to have dry boots again. Dinner was equally satisfying: pasta, whale meat, and wine.

Tasilaq looks like something out of a storybook. The houses, painted in bright primary colors, resemble LEGO blocks scattered across the hillside. From certain vantage points, the town appears to sit on a lake rather than a fjord, as the water widens at its end.

As the largest town in East Greenland with a population of 4,500, Tasilaq felt like any small town—friendly, lively, and full of curious travelers. Locals greeted us as we passed, and tourists often stopped to ask where we were from and what kind of expedition we were on.

We visited the Tasilaq Museum, an eye-opening look into Inuit culture. Much of what we learned revolved around survival in the Arctic, where every tradition is shaped by necessity. For instance, a man could take a second wife—but only if he was a skilled hunter. It made perfect sense: he would need to provide for a larger family, and his kills required multiple hands to clean and process.

The artifacts on display were both ingenious and humbling. A traditional kayak made from sealskin looked impossibly light and unstable—I couldn’t imagine keeping it upright, let alone using the attached harpoon while hunting. We learned why the Greenlandic paddle, still used today, is preferred over modern designs: it moves through the water more quietly, making it easier to sneak up on prey.

One artifact stood out above all others—a narwhal tusk nearly twice the height of a person. But the most fascinating piece was an Inuit map, hand-carved in wood, its ridges and contours mirroring the actual bumps and bays of the coastline. It was a reminder of how people had navigated these waters long before GPS—or even paper maps—ever existed.

Arctic Wildlife: Sparse and Relentlessly Hunted

The most prevalent wild creature we encountered in Greenland, much to our dismay, was the mosquito. The moment we stepped onto land, they swarmed around us, forcing us to don mosquito nets within minutes. Fortunately, they were more of a nuisance than a real threat—so slow that they rarely managed to bite.

The next most common animal we saw was the Greenlandic sled dog. Though not wild, these sturdy dogs are a unique breed, integral to life in the Arctic. Nearly every house had dogs tied outside, and just beyond the towns, we saw large clusters of them. As we entered Tasilaq, a pack of barking dogs greeted us, their voices carrying over the landscape. Only the puppies roamed freely—adorable, playful, and as curious as any young creature.

We spotted a few whales and seals, but, sadly, we saw more evidence of them being hunted than alive in the water. Whale bones lay scattered near every settlement. In the harbors, dead seals were tied up in the water—a traditional method of preservation. One time, we saw seven or eight seals bound together, floating just below the surface.

Hides were a common sight, too—several seal skins stretched and drying. In Tinitilaq, we saw a polar bear hide hanging out to dry. It was massive, thick, and plush—a striking sight. But as magnificent as it was, I couldn't help but think it would be better left on a living bear. Yet, this is the Inuit way of life, a hunting culture deeply woven into their survival and traditions, one they strive to preserve and pass down to future generations.

End of the Journey: Gratitude, Solitude, and the Call to Go Further

East Greenland is a place of staggering beauty—wild, raw, and untouched. The silence, broken only by the distant crack of calving ice, the blow of a whale, or the whisper of wind over the fjord, holds a power that lingers. It’s a landscape that makes you feel small in the best possible way, a reminder that nature still reigns in some corners of the world.

This kayak expedition in East Greenland reaffirmed and deepened my love of expedition kayaking. The rhythm of the paddle, the glide of the boat over water, the self-sufficiency of carrying everything needed to exist in the wild—it all feels right. There’s a simple clarity in moving through a place under your own power, where the only goals are to keep going, to take it all in, and to be fully present.

Since this trip, every time I launch my kayak into the water, the feelings I discovered in Sermilik Fjord return—joy and peace. It’s the deep, steady contentment of being exactly where I’m meant to be. That feeling stays with me, just like the Arctic itself.

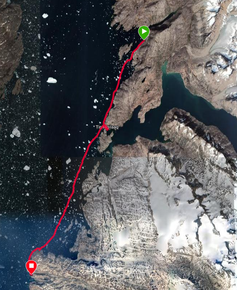

Kayak Route Maps

This expedition comprised a total 124 km of paddling and 22 km hiking

Day 1, July 28 - 13.79 km

Day 2, July 29 - 14.58 km

Day 3, July 30 - 27.68 km

Day 4, July 31 - 28.74 km

Day 5, August 1 - 25.67 km

Day 6, August 2 - 13.76 km

Day 7, August 3 - 22 km

Comments