Kayaking the Orca Highway: A Wilderness Expedition Along Vancouver Island’s Remote North Coast

- Ruth Bergman

- May 9, 2025

- 12 min read

In Pursuit of Orcas: Drawn to Vancouver Island’s Remote North

What I love most about kayak expeditions is the long, quiet hours on the water—just the rhythm of the paddle, the hush of wilderness, and the steady immersion in the natural world. There’s a kind of peace that settles in when you're that far removed from noise, from crowds, from urgency. And then, if you're lucky, that peace is broken in the best possible way: by the sudden breath of a whale, or the characteristic curve of a humpback’s gray fin and tail slipping beneath the surface. And, if you’re exceptionally lucky, by the towering dorsal fin of a male orca.

We’d paddled in whale territory before—off the coast of Iceland, through the fjords of Greenland—and while those trips were unforgettable in their own right, the whales always felt like whispers just beyond reach. A distant spout. A lucky glimpse. Stories from other paddlers of closer encounters. Again and again, we heard one name come up: Vancouver Island. If you really want to see whales—especially orcas—everyone said, that’s the place. So of course, we had to go.

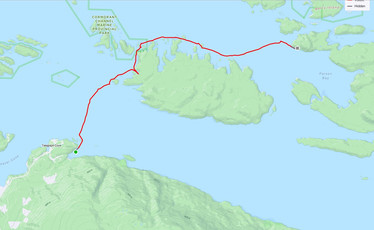

We chose to go with At the Water’s Edge Adventures (AWE), a small outfitter recommended by our friend Erik. They specialize in fully self-supported expeditions, and we worked with them to design a custom 8-day route through two very different worlds: the bustling orca thoroughfare of Johnstone Strait—one of the best places in the world to see orcas in the wild—and the quieter, more remote Broughton Archipelago, a maze of forested islands known for their striking coastal beauty and deep Indigenous cultural history.

Into Orca Waters: Launching from Harbor Bay

We spent the night before our launch in Telegraph Cove—a destination in its own right, especially if you're a fisherman. It’s a tiny boardwalk village tucked into a sheltered inlet, where weathered wooden buildings lean companionably against each other and the docks are lined with boats ready to head out into whale-rich waters. It feels like a place caught between eras—part working harbor, part tourist attraction—but with a laid-back charm that sets the tone for adventure.

The next morning, we made our way to At the Water’s Edge Adventures—quite literally at the water’s edge, on a quiet beach just outside the heart of the cove. We arrived with just a few bags; AWE provided everything else for the expedition. The gear—kayaks, paddles, tents, dry bags, camp chairs—was top-notch, clearly chosen by people who’ve spent serious time living from a boat.

We did have one surprise waiting for us: a double kayak. I’ve never understood the assumption that couples want to paddle together. One firm comment later, the tandem was whisked away and two single kayaks took its place. Lesson learned: always clarify that detail when booking.

Within a couple of hours, we’d met our guides, gone through a safety briefing, packed the boats with gear, food, and water, and were ready to launch. As we slid away from the shore and into the calm of the cove, the scope of the journey ahead opened up in front of us—eight days of paddling, camping, and exploring in one of the richest marine ecosystems on Earth. And it would begin with a long day’s paddle.

The Orca Show: A Spectacle of Whales and Watchers

Almost as soon as we left the protection of the cove and got our first full view of Johnstone Strait, it was clear something was happening. Boats were converging from every direction, slowing to a stop mid-channel. The radio crackled to life with a flurry of chatter. Then our guide turned and shouted, “The orcas are coming!”

In northern British Columbia, resident orcas travel in large, closely knit pods. When a pod moves through the Strait, following salmon runs up or down the coast, it’s not just a few whales—it’s dozens. We might see 50, 80, or even more slicing through the water in steady, synchronized waves. During our time in Johnstone Strait, this incredible phenomenon happened several times—on the first days, and again on the final two days of our expedition.

When orcas are spotted, the word spreads quickly over marine radio. After all, nearly everyone is out there hoping for just such a moment—and most are only on the water for a few short hours. So when the call goes out, the crowd gathers. The still water of the Strait transforms into a kind of aquatic theater, with dozens of boats and clusters of kayakers watching in awe as the whales glide by. We saw towering male dorsal fins, male and female pairs, mother-and-calf pairs, and sleek bodies surfacing in every direction. It’s not a quick event—these pods take their time. You can easily spend half an hour simply watching the procession move past.

When the last fin dips below the surface and the boats begin to disperse, we’re left grinning, wide-eyed, trying to put the experience into words. That first close encounter is a shock—a thrill that catches you off guard. And while the surprise fades with each encounter, the anticipation and the joy never do.

Predators in Motion: Witnessing Transient Orcas Hunt

We were still processing the spectacle of the massive resident orca pod—and the unexpected cascade of dolphins that streamed past in their wake—when the calm was interrupted again. A few boats began to gather offshore as we paddled quietly along the rugged coast of Hanson Island. Our guide pointed to a familiar research vessel in the distance. “They’re follow the Biggs,” he said.

Unlike their salmon-hunting cousins, Biggs—or transient—Orcas are apex predators that specialize in marine mammals. They follow prey across vast stretches of ocean, and their movements are harder to predict. Their pods are smaller, their behavior more secretive, and their presence often signals drama beneath the surface.

It didn’t take long to realize we were in for something special. The research boat was shadowing a pod of transients making their way up the channel, and we followed from a respectful distance. Every so often we’d catch the arc of a dorsal fin or the rush of a spout. Then the whales stopped—just offshore in a small, protected bay—and so did we.

This was no tranquil migration. The pod—four or five individuals, all female—moved with restless energy, sweeping back and forth across the bay in a way that felt...intentional. They surfaced irregularly, dove suddenly, and kept us guessing. The tension was palpable.

And then it happened. All at once, the orcas surfaced in perfect formation, shoulder to shoulder, and charged toward the shore at full speed. There was no mistaking it—this was an attack. We sat frozen in our kayaks, mesmerized, watching pure predatory power in motion. It was fast, silent, coordinated—and over in seconds.

We never saw the target and couldn't say whether the hunt was successful. The orcas continued north, apparently. We did too, still buzzing with adrenaline, trying to absorb what we’d just witnessed.

Not long after, we heard spouts again—and realized the pod was now headed straight toward us. At one point, they surfaced just twenty meters from our boats. I didn’t even reach for my camera. I was too busy watching, too caught in the moment to do anything but smile.

It was an extraordinary day—one that left us speechless and stunned, with the rare privilege of having seen the wild in action.

In Tune With the Sea: Listening to the Wild

Over eight days of paddling, no two were the same. The geography shifted constantly—from the dense, island-choked waterways of the Broughton Archipelago to the wide-open stretches of Johnstone Strait and George Passage. But through it all, one element remained constant: the quiet. Not silence, exactly, but a spacious hush, broken only by the sounds of the sea.

The most persistent presence was the humpback whales. We heard them more than we saw them—sonic companions who surfaced just out of sight. The deep, echoing burst of a spout would drift over the water, sometimes far off, sometimes startlingly close. There might be a thunderous splash of a breach or the sharp crack of a tail slap. Often, the sound came first—and left us scanning the horizon, eager for a glimpse.

Birdlife was another constant. We passed shorelines busy with oystercatchers, herons, and gulls, and watched seabirds wheel and dive over open water. Our guide pointed out large flocks circling in tight spirals—a sign that a humpback might be bubble-net feeding below, herding fish into a dense school. We paddled quietly, hoping for a chance to see one rise open-mouthed through the frenzy.

Seals and sea lions followed us often, surfacing with noisy splashes and curious eyes. Usually they were playful or mildly inquisitive, trailing our boats from a distance. But when we neared their rookeries, the behavior altered. Dozens of heads would rise at once in a defensive line—a living barricade in the surf. It was strangely mythic, like something out of ancient seafaring lore. Our guide suggested that this sight might have inspired the multi-headed Hydra.

We’d come across a particularly agitated group of sea lions. Their behavior stood out—loud and aggressive. At the time, we were puzzled. Only later, when we witnessed a pod of Biggs orcas hunting in the same waters, did it click. These sea lions were on high alert for good reason. They were being hunted.

This ever-changing soundscape became the pulse of our journey—an immersive, living symphony. The spouts of humpbacks, the cries of seabirds, the splash of sea lions, and the steady dip of our paddles composed a soundtrack that filled the space around us, often more vivid than the scenery itself. It was as rich and unpredictable as any concert, and the wildlife encounters—unfiltered and unchoreographed—felt more intimate than any ballet.

Through the Archipelago: Kayaking Through Calm and Currents

While the orca sightings in Johnstone Strait were unforgettable, kayaking through the Broughton Archipelago offered its own kind of magic. This was a paddler’s paradise—a labyrinth of forested islands, narrow tidal channels, and intricate waterways. Each day brought new routes, new wildlife, and constant calculations. We shaped our days around the tides and currents, timing our crossings to ride the flow rather than fight it.

Every island felt like its own world. Dense with coastal beauty and alive with motion—eagles overhead, birds calling, otters slipping in and out of sight—each shoreline seemed to hold something unexpected. One morning, paddling a tight channel, Oren spotted a baby bear ambling along the rocks. We stayed well offshore—half entranced, half on edge—scanning the trees for any sign of a protective mother.

On the third day, the wind had picked up. It barely touched us as we threaded between islands toward camp. After a late lunch, we set off to circumnavigate our little island—a short paddle, just for fun. But the moment we slipped out of the sheltered channel, conditions changed. The current pushed us swiftly forward, carrying us deeper into the archipelago. We laughed at the unexpected speed but quickly realized we were drifting too far.

Turning back was another story. We now faced the current—and as we rounded the island’s edge, a headwind hit us hard. One-meter waves rolled at us, turning our playful jaunt into a full-body effort. Fifteen minutes felt like fifty. Then, just as suddenly, we rounded another corner, caught the wind again, and glided straight to shore. One moment the tents looked distant; the next, we were crunching into the beach.

Each day brought its own surprise. A change in the weather. A new current. A bear, a whale, a perfect cove. Every corner of the archipelago had its own rhythm—its own gift waiting to be discovered.

Fogbound: Learning to Paddle Without Sight

On day six, the fog descended thick and fast. We had a long paddle ahead—to a small rock island in the middle of the channel—and began our journey through a soft grey silence. As we moved between the islands, we could just make out their forested edges, blurred like brushstrokes in watercolor. But when we reached the open passage, visibility vanished. Nothing but white.

Our guides gave clear instructions: stay tight, between their two kayaks. They navigated by compass and map, maintaining orientation where sight couldn’t. For an hour, maybe two, we paddled without seeing more than the tips of our companions’ kayaks.

Somewhere in the distance, then closer, then closer still, came the sound of a humpback whale. One spout, then another. The sound grew louder and closer—so close. And then, it surfaced. A massive humpback broke the water not twenty meters away from me, smooth, sinuous body emerging from the fog. Then it was gone again, as if swallowed by the mist.

It’s not easy to trust in a direction when everything looks the same. In a full whiteout, there is no sense of progress, and you begin to wonder: are we truly heading anywhere at all?

Then a darker patch appeared in the haze, just a shade deeper than the fog around it. Slowly, it took shape. A shoreline, a forest, a landing point. We had been headed in the right direction all along.

As the fog began to lift, a pale arc appeared—a fogbow. At first faint, then unmistakable as the sun’s glare grew, it stretched across the mist. Formed by sunlight hitting tiny droplets in the fog, it hovered above the water—a rare and beautiful surprise.

Rain or Shine: Life on the Islands

Ours was a self-sufficient expedition, the longest we’d done to date—eight days in the wild, carrying everything we needed. Well, almost everything. Though the trip felt remote, we were a short boat ride from Telegraph Cove, and we did get resupplied once or twice. Still, each time we landed on an empty beach and set up camp, it felt like discovering a new world.

With one exception—our campground on Johnstone Strait—every site was on a small island entirely our own. On the first two nights, it rained steadily, and our guide wisely kept us in the same campsite to avoid packing up wet gear. We pitched our tents in the forest just behind a sandy beach. Every walk back to shelter was a miniature nature hike through ferns and under dripping boughs, dodging slugs and admiring the shy presence of birdsong. The sounds of the island carried into the night. In the dark hours, we lay still and listened to the whoosh of humpback spouts echoing across the water, punctuated by occasional low vocalizations.

The most unforgettable campsite of the trip was barely an island at all—just a rock in the middle of the channel. We circled it in fifteen minutes to choose where to pitch our tent. The sea was visible from every direction. We arrived in time for a late lunch and spent long, quiet hours afterward listening to the marine soundtrack, watching the fog roll in and out, and greeting the sea lions and humpbacks who passed by like familiar neighbors.

The Group That Glides: Expedition Camaraderie

On a trip like this, the group dynamic can make or break the experience. Fortunately, we were in good company. In my experience, people who sign up for an eight-day wilderness kayaking adventure tend to be the kind you’re happy to share a beach with. This time, we knew we were in for a good ride as soon as everyone unveiled their contributions to the expedition bar on day one.

The paddling wasn’t grueling. We usually landed early enough to snag a campsite, settle in, and snack before dinner. That left us with long afternoons to chat, explore, or lounge with warm drinks in hand. We were only five, and it was a eclectic mix. One teammate was working to restore an 80-acre forest—his stories were full of slow victories and stubborn underbrush. Another had tales from small claims court, equal parts hilarious and tragic. There were campfire debates on world politics, deep dives into nature documentaries, and even a campfire physics lecture, courtesy of Oren.

And then there was the food. Our guide set a new bar—no pun intended—for wilderness dining. This wasn’t just “good for camping” food. It was good, full stop. Thoughtful, home-style meals that always had a finishing touch—fresh herbs, bright fruit, the occasional unexpected garnish. French toast came with maple syrup (of course, we were in Canada) and a handful of summer berries. One morning, shakshuka made an appearance, steaming and spicy. Thanks to a vegetarian paddler, many meals were meatless and delicious. Smoked tofu, I discovered, is surprisingly tasty. Each meal somehow managed to outdo the last. And somewhere between the shared stories, warm meals, and steady rhythm of the sea, we found ourselves well-nourished in every sense—body and spirit

Solitude and Spectacle: Reflections from the Orca Highway

The Broughton Archipelago offered the kind of wilderness you rarely find anymore—quiet, untouched, and expansive. Some days we paddled for hours without seeing another soul, just weaving between islands, immersed in stillness broken only by the call of a bird or the exhale of a whale. That solitude, especially paired with the rhythm of paddling, settles into your bones. It clears your mind.

Then there was Johnstone Strait. Still part of the wild, but filled with people—boaters, kayakers, whale watchers—all drawn here by the same promise: orcas. When the word gets out that a pod is on the move, the strait transforms into a stage. Boats gather. Cameras click. And for a moment, nature becomes performance. It’s awe-inspiring, but not quiet.

And maybe that’s the story of this place. The tension between peace and presence. Between wildness and wonder. Between being alone and being part of something shared. We came seeking solitude, and we found it. We came chasing orcas, and they gave us a show. We left with something else entirely—eight days of living in rhythm with land and sea, and the kind of clarity that only comes when you're out there long enough to let the noise fall away.

Resources

Comments